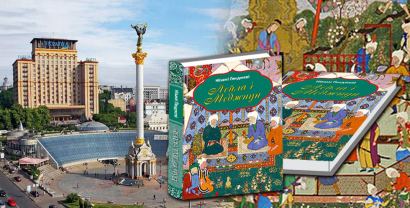

Nizami Ganjavi’s Epic Love Poem Released in Kyiv

The Azerbaijan State Translation Centre (AzSTC) is pleased to announce the printed edition of Leyli and Majnun by Azerbaijan’s greatest poet Nizami Ganjavi due to the announcement of 2021 as a “Year of Nizami Ganjavi” in Azerbaijan.

The epic love poem was published in Ukrainian by the Kyiv-based publishing house “Yaroslaviv Val”. The translator of the poem is Leonid Pervomaisky, an outstanding poet and translator from Ukraine. Agafangel Krimsky penned the foreword to the book edited by Grigory Guseinov.

Foreword

Studying Nizami’s Legacy

Nizami Ganjavi, in full Sheikh Nizameddin Abū Muḥammad Ilyās ibn-Yūsuf ibn-Zakkī ibn Muayyad Ganjavi (1141–1203), was Azerbaijan’s romantic, more precisely Sufi poet. Widely regarded as one of the greatest literary grandmasters in history, Nizami was an inexhaustible source of imitation for later romantic poets in the Persian language, whereas representatives of Turkic literature benefited from his legacy. As few facts are known about Nizami, his contemporaries, as well as historians and literary critics who lived in the days of Nizami, were unable to have adequately addressed his life and biography.

The first article on Nizami’s biography, more or less accurate and logical, was written almost three hundred years after the poet's death. An anthological and compilative journal titled “Tazkiratash-shuara” (“Memory Notes About Poets”) issued in 1487 and devoted to the Dovletshah poets’ (XV century) biographies originally from Central Asia (Samarkand) dedicated a three-page section to Niiown work,lared zami. While the Dovletshah’s article is far from perfect, there are several valuable points in the article. For example, the author notes that Nizami is close to the hardworking Sufi brotherhood. One of the important points is the Dovletshah’s quotation that Nizami and his brother, the poet Kiwami, had a common (possibly genealogical) nickname Mutarrizi, and the logical consequence of this is that we can come to interesting genealogical conclusions about the origin of this family.

Aufi, a contemporary literary historian and anthropologist, included only Nizami’s work in his historical and literary anthology, but not the poet’s biography. Only after the death of this great Azerbaijani poet, Aufi finished the work “Lubāb al-albāb” (لباب الالباب). But the works were undoubtedly collected during the poet's lifetime. Aufi published three lyric poems by Nizami in his journal. The third poem written in the genre of a short elegy was devoted to the untimely death of the poet’s son at a young age. This elegy describes how the son took his rightful place among the happy, shining inhabitants of Paradise, and the father who couldn't stand being apart any longer wept with tears of blood.

Jami, the poet and historian of the late 15th century, without any information about Nizami’s biography at all repeats Aufi. In “The Seventh Garden” (“Baharistan”,1487), i.e. in the 7th chapter, Jami makes valid excuses for his silence, without giving any factual information about the poet's life. Personally, we take Jami’s these words at least as an excuse: “Nizami’s brilliant talent, dignity and perfection do not need any explanation. After all, no one is able to bring such pleasurable experience, to inspire elevated feelings. This talent is beyond the human abilities.”

Until the third quarter of the 19th century, the European orientalist science, partly due to Persian sources, did not have a complete and accurate understanding about Nizami’s personality and life. For the first time, Europeans received more or less credible information about Sheikh Nizami from Joseph von Hammer’s work. In the section dedicated to the authors of the XII century, a large part covers Nizami’s work. In Hammer's book, selected samples of Nizami’s work were translated into German and presented in the forms of prose, poetry and summaries. Regardless of how weak (often even inaccurate and incorrect) Hammer's translations may have been, the author managed somehow to acquaint Europeans with Nizami's legacy in a positive light. Although Hammer's translations did not reflect peculiarities of Nizami’s genius, Goethe, the genius of German poetry, praised Nizami a year later in his book “The Divan of West and East”, referring to the awkward examples given in Hammer's History of Persian Literature, and named him ‘a poet of gentle spirit and great talent.’

We can say with certainty that a more thorough study of Nizami’s heritage began only in 1871, when Wilhelm Bacher, the young scientist, wrote his thesis “The Life and Work of Nizami”. Nizami’s autobiographical details given in the epic poems of “Khamsa” helped him greatly while studying the poet’s lyrical digressions. Trying to combine important information collected from Nizami’s works into a single composition, to adapt it to historical period, Bacher managed to create a work which is still considered as the main source from a scientific and methodological point of view.

Y.E. Bertels was amongst the first who tried to acquaint the Russian readership with Nizami’s poem “Seven Beauties.” This was a prosaic translation of the fourth beauty’s story in the blue castle. As we know, later Bertels repeatedly turned to the great Nizami heritage. In his other work, the author gave a very concise, but accurate and scientifically flawless page about Nizami: “Nizami is also distinguished by great knowledge on using expressions based on sensitive psychologism, and his imitators, instead of focusing on these qualities, care only how his poems are pleasing to the ear, and the style is complex...”

On the eve of the 800th anniversary of the great Azerbaijani poet Nizami, interest in the poet’s creativity increased in scientific circles. There are three or four monumental books related to this significant event to be mentioned. One of them is the “Anthology of Azerbaijani Poetry”, edited by V.A. Lugovsky and Samed Vurgun. The book has a special section devoted to Nizami, and the preface to his selected works contains thoughts about the great poet. One of the indisputable ideas in the article about Nizami is that, despite the fact that the poet wrote his work in Persian, he always remains the poet of his native Azerbaijan. Thus, the history of Azerbaijani literature development begins not from the time when this people wrote in Turkish, but from the pieces of other local authors that came to us from earlier times (though they wrote in Persian), as well as the works of ancient Albanian authors.

One of the valuable research works is “The Great Azerbaijani Poet Nizami” by Y.E. Bertels. As the continuation of the book, the author wrote three more articles: “Some points while exploring Nizami’s heritage”, “Sources in Leyli and Majnun”, and “Nizami and Firdovsi.”

I feel bound to say a few more words. My views on documentary facts, which demonstrate in detail and truthfully that the Mutarrizi dynasty that moved to Ganja, the poet’s homeland in Azerbaijan at the beginning of the 12th century, has a Turkic, possibly Turkestan origin, can be of interest as a biographical discovery and as a novelty.

I tried to closely connect different moments of his life and literary activity with the social characteristics and views of the Sufi brotherhood that the poet joined from a young age. In the previous chapters, after getting acquainted with the studies of European scientists on Nizami, I turned my attention completely to the study of the general picture of the political and spiritual life of Iran and Azerbaijan associated with it during the period of the Seljuk.At that time, in the XII century, Azerbaijan enjoyed the rich benefits of All-Iran or Persian-Arabic culture of the Middle East in a broader sense and made a significant contribution to this treasury. A world-level genius Nizami grew up in such an environment. Not by coincidence, Nizami is regarded as a source of pride for both his Homeland Azerbaijan and Iran that accepts his creativity native to itself.

AND OTHER...

-

Book “Fuzuli’s Creativity” by Mir Jalal Out in Jordan

Book “Fuzuli’s Creativity” by Mir Jalal Out in Jordan

The book “Fuzuli’s Creativity” by the famous Azerbaijani writer and literary scholar Mir Jalal, which tells about the works of the brilliant Azerbaijani poet...

-

Yusif Vazir Chamanzaminli’s Creativity in the Israeli Literary Magazine

Yusif Vazir Chamanzaminli’s Creativity in the Israeli Literary Magazine

“Artikl”, the popular Israeli literary magazine, has posted in Russian an excerpt from the novel “In the Crossfire” by Yusif Vazir Chamanzaminli, the outstanding...